“Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples” is a seminal work by Linda Tuhiwai Smith that explores the impact of colonialism on research methodologies and offers alternative approaches to research that center the knowledge and experiences of Indigenous peoples.

The book begins by providing a critical analysis of colonialism and its impact on research methodologies. Smith argues that research has been used as a tool of colonialism to reinforce the dominant narratives of the colonizers and marginalize the knowledge and experiences of Indigenous peoples. She argues that research must be decolonized in order to center the knowledge and experiences of Indigenous peoples and challenge the power dynamics of colonialism.

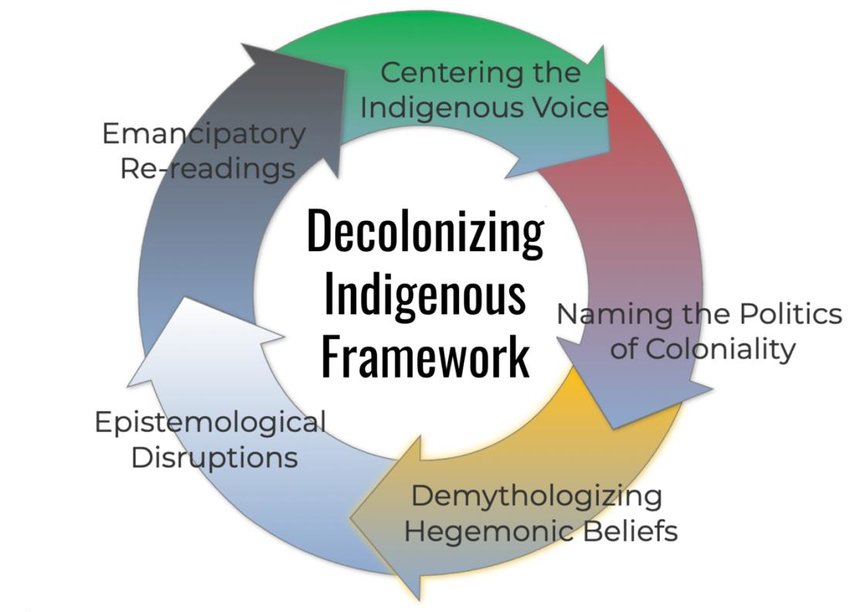

Smith provides a framework for decolonizing research methodologies. This means that she offers a set of guidelines and principles for conducting research that challenges the power dynamics of colonialism and centers the knowledge and experiences of Indigenous peoples. One key aspect of Smith’s framework is the importance of critical self-reflection. She argues that researchers must examine their own biases and assumptions in order to avoid reproducing the dominant narratives of colonialism in their research. This means that researchers must be aware of their own positionality and how their social location, experiences, and beliefs might shape their research. Another key aspect of Smith’s framework is the importance of collaboration with Indigenous communities. She argues that research must be conducted in a culturally appropriate and respectful manner, which requires working closely with Indigenous communities to ensure that their voices are heard and their perspectives are taken into account. This means that researchers must engage in a process of mutual learning, in which they learn from Indigenous communities and work together to co-create knowledge.

Smith emphasizes the importance of centering the knowledge and experiences of Indigenous peoples in research. This means that researchers must recognize and value the knowledge systems, perspectives, and experiences of Indigenous peoples and work to incorporate them into their research. Smith argues that Indigenous knowledge is just as valid as Western knowledge and should be treated with the same level of respect and consideration. However, colonialism has historically marginalized Indigenous knowledge and placed Western knowledge systems as the dominant and authoritative sources of knowledge. Smith challenges this narrative by advocating for a more equitable and collaborative approach to research that values and respects Indigenous knowledge. Creating spaces for Indigenous voices to be heard means actively seeking out the perspectives and experiences of Indigenous peoples and integrating them into research. This requires engaging in a process of mutual learning, where researchers listen and learn from Indigenous communities and work collaboratively to co-create knowledge. By centering Indigenous knowledge and experiences, researchers can challenge dominant narratives and create a more inclusive and equitable research process.

One of the strengths of the book is Smith’s ability to make complex theoretical concepts accessible to a wide audience. She uses clear and concise language to explain the impact of colonialism on research methodologies and offers practical advice for decolonizing research.

Another strength of the book is its relevance to a wide range of fields, including anthropology, sociology, education, and environmental studies. The book offers insights into the ways in which colonialism has shaped research in these fields and offers practical strategies for decolonizing research methodologies.

Finally, this book is a must-read for anyone interested in research methodologies, social justice, and decolonization. Smith’s insights into the impact of colonialism on research methodologies are profound and her framework for decolonizing research is practical and actionable. This book has the potential to fundamentally transform the way we think about research and its role in society.